Some twenty years ago a small meeting convened in Budapest bringing together delegates from different countries and institutions. While each put forth their unique perspective, they also shared a mutual belief in what they would soon come to coin ‘Open Access’.

The group of delegates met with the intention to accelerate global efforts to make research articles in all academic fields freely available on the internet and the result of that meeting was the formalisation of the Budapest Open Access Initiative, commonly referred to as the BOAI.

The group then released a declaration or statement of strategy and commitment to advocating for and realising Open Access infrastructures across diverse institutions around the world.

How did the BOAI meeting come about?

The Budapest Open Access Initiative (BOAI) was borne out of a meeting that the Open Society Foundation (OSF) organised in Budapest, having been based there up until 2018 when it finally moved to Berlin. The foundation supported the Network Library Program which worked in 24 countries across Central and Eastern Europe as well as the former Soviet Union and supported the science journals donations program through which they shipped hard copies of scientific journals to academies of sciences in these regions.

In 2000 the OSF’s board challenged them to find new ways to get academic literature into the hands of researchers who needed it, besides physically shipping these hard copies of journals. The meeting was also inspired by a petition which PLoS, the Public Library of Science, had released in the summer of 2001. This called on academics to withhold submissions from academic journals which did not make the resulting articles freely available after six months.

This culmination of forces together encouraged the OSF to seek out alternative solutions, starting with a clarion call to leaders across the gamut of scholarly communications, to see how they could best advance the goals that they were beginning to define as a community. During these formative stages, all participants agreed that any movement towards realising improved access to research materials needed to be global in its implications, in order to have a wide and lasting impact.

Agreeing on a common definition

Prior to the contemporary understanding of the term ‘Open Access’, practioners such as Peter Suber often referred to the concept of the free sharing of research material online as ‘Free Online Scholarship’. As the meeting convened in Budapest however, participants considered the antecedents of the new and growing movement in research and found areas of common ground with open source software development, a term, practice and movement which was already recognised in its own right.

The meeting in Budapest aimed to explore a similar kind of openness but with a focus on research texts and eventually research data. Finally, the term Open Access, while not quite as self-explanatory as initially hoped, was at least short. The participants agreed on the term, by analogy to the open source movement, and went on to define it:

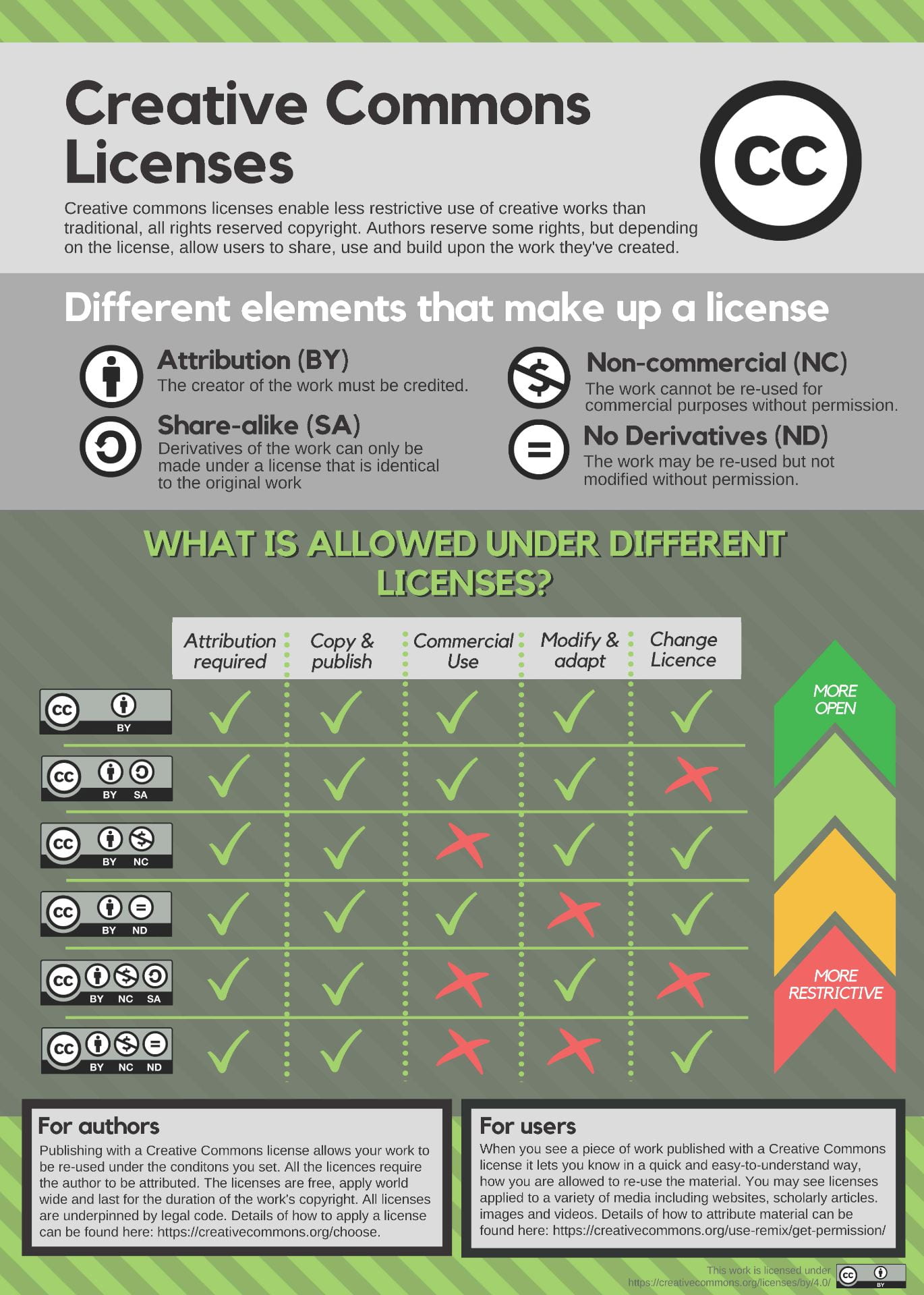

By “open access” to this literature, we mean its free availability on the public internet, permitting any users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of these articles, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without financial, legal, or technical barriers other than those inseparable from gaining access to the internet itself. The only constraint on reproduction and distribution, and the only role for copyright in this domain, should be to give authors control over the integrity of their work and the right to be properly acknowledged and cited.

–The Budapest Open Access Initiative

The Strategic goals

A manifesto also emerged, as part of a collaborative writing endeavour, to express the delegates’ thoughts coming out of the meeting in Budapest. One of the issues which preoccupied them was agreeing on the means upon which to best achieve Open Access. The first strategy involved posting a copy of an article to an institutional or subject-based repository. The second strategy involved publishing in an open access journal. (‘Open Archives’ for instance had previously been suggested as another alternative definition to ‘Open Access’ but would have favoured the repository approach). Eventually the two routes to achieving Open Access were advocated for and these are widely referred to today as Green and Gold Open Access respectively (and were objects of attention in the later Finch report of 2012).

Moving forward

Throughout the BOAI meeting in 2002, the overriding questions that emerged included: were the participants’ visions compatible; could they work together; could they agree on common definitions. And the answer was yes. Today, Open Access practices and movements are beset by new challenges which once again highlight the need for global input and action from activists and scholar-led communities. These questions frame ‘Open Access’ not as an end goal but as a means to achieving equity (insofar as it can) as well as quality in research and scholarly communications.

On 14 February 2022, The Budapest Open Access Initiative will celebrate its 20th anniversary and in preparation, the BOAI2020 steering committee is working on a new set of recommendations, based on BOAI principles, current circumstances, and input from colleagues in all academic fields and regions of the world.